Community Health

PRASAD Chikitsa’s Community Health Programs are effective because they are comprehensive and far-reaching. Our community medical programs meet people’s immediate health needs such as illnesses and injuries, while the preventive initiatives are achieving long-term, sustainable improvements in the welfare of individuals and communities.

PRASAD Chikitsa’s approach to Community Health Care is holistic; we respond to people’s physical and mental health concerns and to the social and environmental conditions that contribute to those concerns.

PRASAD’s Family Health Center is home to many of those initiatives, including the Reproductive and Child Health Program, Accredited Social Health Activist Training Program and the School Health and Nutrition programs.

Reproductive and Child Health (RCH)

The Reproductive and Child Health Program was launched in 2002 in order to instruct pregnant women on the importance of coming for regular prenatal checkups, so that the staff there can detect and manage any serious complications. The second objective is to teach expectant mothers about childcare, nutrition, hygiene and other topics, so that they have healthy pregnancies and safe deliveries.

Activities of the Reproductive and Child Health Center include:

Training PRASAD Chikitsa staff in prenatal, natal, neonatal and postnatal care

Training PRASAD Chikitsa staff in prenatal, natal, neonatal and postnatal care

Training Accredited Social Health Activists (an enhancement of the former Dai Program)

Setting up transportation links between remote villages and the nearest medical facilities

Maintaining a referral system with links to nearby obstetrics facilities, primary health centers, and rural private and government hospitals

Forming working partnerships and liaisons with other agencies and programs in the field of maternal child care

Since the RCH program began, more than 2,000 women have participated, with tangible, positive results. Among the program’s achievements has been a significant increase in the number of infants whose birth weight exceeds the Indian national average birth weight of 2.7 kg (just under six pounds.)

Accredited Social Health Activist Training

The PRASAD Chikitsa Reproductive Child Health program was established in 2002, and Midwife or Dai Training has always been a key component. As of 2011, we expanded the curriculum into training for Accredited Social Health Activists or ASHAs.

Social Health Activist (Arogyyavardhinis) Training

At PRASAD Chikitsa’s Family Health Center, the Midwife or Dai Program has evolved into the Accredited Social Health Activist or ASHA Training. They are known locally as Arogyavardhinis.

This training program is still part of the Reproductive Child Health program. It continues the Midwife Program’s intense focus on reducing maternal and child mortality rates and ensuring the health and well-being of the mother, child and family.

Just as a Midwife would, an ASHA counsels women on birth preparedness, the importance of safe delivery, breast-feeding, bottle-feeding and the care of young children. ASHAs also teach women about immunization, contraception and preventable infections.

One goal of India’s National Rural Health Mission is to provide every village in the country with a trained, female ASHA, and PRASAD fully supports that goal; in 2010 alone, we trained more than 260 ASHAs for villages in our catchment area.

The PRASAD ASHA’s role has a much wider scope though, and so PRASAD Chikitsa expanded the training beyond the Indian Government’s ASHA training module. The PRASAD model incorporates new elements of public outreach and education.

Each PRASAD ASHA works with the people of her own community. She provides information on health standards such as nutrition, basic sanitation and hygienic practices and healthy living and working conditions. She also helps people gain access to government services such as immunization, pre-and-post natal check-ups and supplementary nutrition. ASHAs even work with PRASAD’s Self-Help Groups, women’s health committees, village leaders and Day Care workers, to encourage villagers to use all the services available to them, to generate lasting, community-wide improvements to their health, safety and quality of life.

Clean Water

Many of us take access to clean, safe water for granted, yet, in India, the second most populous country in the world, it is estimated that three-quarters of its drinking water is contaminated. According to World Bank estimates, one in five cases of communicable disease in India is attributed to contaminated water. In the rural Tansa Valley, the health of the residents is often adversely affected by waterborne diseases such as cholera, dysentery and typhoid.

The situation worsens with the deluge of monsoons, which muddy and further contaminate the water, increasing the possibility of waterborne illness. The impact goes beyond compromising health, livelihoods are also threatened among people who cannot afford to miss a day of work.

Since launching the Clean Drinking Water initiative in 2014, PRASAD Chikitsa has emphasized the importance of clean water and distributed 747 water purifiers throughout the Tansa Valley, educating villagers on their proper use. The easy-to-use filters are life-changing, making water, a basic human need and right, safe for consumption.

Sanitation

Unsafe water, poor sanitation and lack of hygiene are still common causes of illness and death. Many of these diseases are preventable.

‘Bang for development buck’, investing in water and sanitation is high on the list. A cost benefit analysis by the World Health Organisation [WHO] stated that each $1 invested could yield an economic return of between $3 and $34 and save up to $7.3 billion per year world wide.

Report on UN Millenium goals on improved water and sanitation for health

The Lancet, vol 365 February 26, 2005

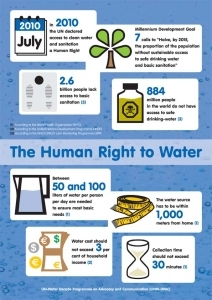

In 2010, United Nations resolution 64/292 recognized the human right to water and sanitation. It also acknowledged that clean drinking water and sanitation are essential to the realization of all human rights..

In 2010, United Nations resolution 64/292 recognized the human right to water and sanitation. It also acknowledged that clean drinking water and sanitation are essential to the realization of all human rights..

Sanitation

More than 72% of the world’s rural people relieve themselves behind bushes, in fields, or by roadsides. Of the 1 billion people in the world who have no toilet, nearly 600 million are in India.

Lack of access to a toilet is a significant public health issue.

India’s population is huge, growing rapidly and densely settled, making it is impossible in rural areas to keep human faeces from crops, wells, food and children’s hands. Ingested bacteria and worms spread diseases, especially of the intestine. They cause enteropathy, a chronic illness that prevents the body from absorbing calories and nutrients. The consistent spread of these diseases helps to explain why, in spite of rising incomes and better diets, rates of child malnourishment in India are not improving faster. UNICEF estimates that nearly one half of Indian children remain malnourished.

Diarrhoea leaves Indians’ bodies smaller on average than those of people in poorer countries where people eat fewer calories, notably in Africa. Underweight mothers produce stunted babies prone to sickness who may fail to develop their full cognitive potential.

Access to toilets is not the only issue.

Defecating in the open can be seen as wholesome, healthy and social. Some cultures see latrines as potentially impure, especially if they are located near the home; or that they are more suitable for women, the infirm and the elderly. It is necessary to educate the population about the health and economic benefits of using toilets and better hygiene. Researchers found that only a quarter of rural householders understood that washing hands helps prevent diarrhoea.

What are the toilets like?

They are not flushing toilets, but rather a two pit latrine with a ceramic toilet plate, housed in a brick enclosure. The waste is directed to one of the pits, which meets the needs of a family of 6 for 18 months or so. Liquid waste seeps though the sides of the brick lined pit, while the solid waste accumulates, and in time becomes rich nightsoil to fertilize farming. When one pit is full, the waste is directed to the other pit, and so on.

How are they built?

Families dig two deep latrine pits and prepare a base for the toilet building. PRASAD staff checks the suitability of the site, provides technical guidance and support during the construction, as well as suitable materials. The materials are provided in two stages and delivered only when the family have demonstrated their commitment by taking the construction to a certain level.

School Health

PRASAD Chikitsa believes that healthy children grow up to be healthy adults, and so PRASAD emphasizes education and prevention just as much as treatment. Every six months, PRASAD conducts health appraisals at schools in 11 villages in the Tansa Valley. The appraisal includes a physical examination, a dental checkup and distribution of medicine and vitamins.

PRASAD Chikitsa also delivers health-related presentations to the children and their teachers. There has been a marked improvement in the children’s health since the program began, when most of the children suffered from scabies, head lice and dental cavities. Today, very few suffer from these afflictions.

Rubella Prevention Program

First arrivals at PRASAD Chikitsa’s first rubella vaccination clinic on 8 December 2015. Now aware of the importance of being immunised, more than the 927 registered flocked to Ganesphuri on the nominated day. Those unable to be treated under the pilot grant, registered for the next clinic, often paying 100 Rupees (about $1.50) towards the cost. showing they regard it as a high priority.

PRASAD Chikitsa medical staff, interns past and present and volunteer staff from Nair Hospital with some of the 1000 young women they processed and vaccinated on one day, 8 December 2105.

Adolescent Health

PRASAD’s medical staff and interns from Nair Hospital conduct regular information and question and answer sessions for adolescents at schools and colleges throughout the Valley. They seek to empower them by giving accurate information about their bodies and this stage of life, and discouraging high risk behavior. Many parents are unable to provide adequate or correct information on these matters.

The topics covered include the menstrual cycle, hygiene, sexually transmitted and reproductive tract infections and diet. The implications of underage marriage are also discussed. A video showing teenage actors dealing with these issues is also shown and is well received. Fears and misconceptions can cleared up. Any cases requiring medical attention were advised to follow up at PRASAD’s Anukampaa Health Centre in Ganeshpuri, or at visits of the Shree Muktananada Mobile hospital.

Underage Marriage

Many young women in rural Maharashtra still marry before the legal age of 18 (46% in 2008). UNICEF reports the numbers are declining slowly, but are still twice as high as in urban areas. These young women are more likely to be uninformed about sex and contraception, have lower self confidence, to make fewer decisions about their own lives, and to believe domestic violence is justified.

In 2008, UNICEF found that 2% of boys in Maharashtra had married under the age of 18.

Informing this vulnerable population and removing taboos against seeking treatment is crucial for public as well as individual health.

For a useful four page overview of the incidence of child marriage, education levels, child bearing and mortality, women’s empowerment and domestic violence see

How Early Marriage Compromises Girls’ Lives, Maharashtra

Youth in India: Situation and Needs, Policy Brief Number 6, 2008, 4pp.

International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai.

A more recent detailed study covering all regions of India

Child Marriage in India

UNICEF December 2012, 102 pp